By Elizabeth S. Craig, @elizabethscraig

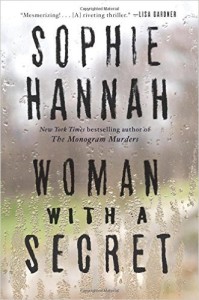

I just finished reading Woman With a Secret (released as The Telling Error in the UK) by Sophie Hannah. I’ve read a fair number of unreliable narrator books lately. This one definitely caught my attention and sustained my interest.

One thing bothered me, as a reader and a writer. There were several points at the end where different police investigators of the murder (and it was a murder mystery, although it could also be called a psychological thriller…more on that later), clearly knew who the killer was. They stated they knew who the killer was, but didn’t let the reader in on it. It’s a quibble. But I’m a mystery writer.

This technique is still, technically, fair play in a mystery. The great Agatha Christie kept her readers on pins and needles as Poirot gathered everyone together in a room to disclose the killer’s identity.

But many modern mysteries allow readers to solve cases alongside the sleuth, letting us in on their thought processes. Since this novel had alternating POVs, readers weren’t always with the sleuth solving the case. We were also in the head of one of the suspects. Readers did have access to the same information that the police did, especially one very clever clue, I thought. The teasers, to me, were frustrating. One of the suspects said that they’d (trying to obscure plot points with a vague pronoun, sorry) figured out why the victim had perished the way he had. Then a detective said the same. Then another detective knew who the killer was.

It was just a little too much teasing for me. I might have been able to overlook one tease, but not several. Because, ultimately, the book was a whodunit. Or was it?

That’s what made me think. If this had been set up as more of a psychological thriller (which some reviews label the book as), then I think I might not have had the expectation that I could solve the case alongside the detective. If we’d had some short bits from the killer’s POV, maybe. But it was set up enough like a traditional mystery/whodunit that I was frustrated by a declaration of the case being figured out—and then a break to an alternating POV.

But the thing is…Ms. Hannah could very well be genre-blending. With thrillers, readers aren’t necessarily trying to solve the crime—frequently we know who the killer is at the beginning of the story. This book had elements of a psychological thriller and elements of a whodunit. Was the author trying to take on too much? Or are mystery readers’ expectations (and mine) too rigid?

As a writer, I strictly follow the tenets of my subgenre, cozy mysteries. The books, honestly, could be read by children because aside from the gore-free murders, there is nothing particularly disturbing about them. No profanity (well, none in all but the first couple of books), no sex, no descriptions of violence. Nothing very dark. The murders occur off-stage. The puzzles are (hopefully) clever and my use of deep-POV is intended to make the readers feel they’re solving the cases alongside the sleuth. My readers have certain expectations associated with the genre and I deliver what they’re looking for. This pleases me too, since I like being especially creative while writing within the limits, within the parameters, of my subgenre’s “rules.”

But I’ve enjoyed books in the past that have done a bit of genre-blending. Paranormal mysteries are fun. Mysteries with a bit of romance offer something a little different. So…is it just a problem when an author dispenses with such a large reader expectation—the almost interactive mystery experience?

I did enjoy the book. It certainly made me think as a mystery writer. My question is this: each genre has its own set of standards or conventions. Should we always pander to reader expectations? Obviously, from an artistic sense, we’re completely free to deviate from the framework. But when is it okay, from a commercial sense, to blur the lines a little with category fiction? How far can we/should we go? Any examples of bestselling books that have really colored outside the lines?

Should we always follow our readers' genre expectations? Click To Tweet

I write space opera, and even that genre blends into others. My books have elements of military science fiction, but I focus more on characters than hard military, and that has disappointed a few readers. But it’s also gained me a lot more, so it was worth it.

Alex–It sounds like you made the right choice here! I usually like focusing on characters, too.

What an important question, Elizabeth! I think there are certain expectations we do have to meet for our readers. For example, readers of your books do not expect, say, grisly descriptions of murder or explicit sex scenes. That’s not what cosy readers want. On the other hand, I think sometimes making people confront their expectations isn’t such a bad thing. Agatha Christie did that with The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, and it was really successful. To me, it depends on what expectation it is, and whether it really adds to the story to mess with it.

Margot–Exactly. Agatha Christie got away with it famously in this example (although there were some who grumbled that it wasn’t fair). Margot and I can’t discuss that more without giving away one of the coolest plot twists in mystery. You put it well…does it add to the story, to the reader experience, to mess with expectations?

I blend mystery, suspense, and romance. My audience, while not huge, continues to grow. My stories are not especially procedural, and are way more the stories of the characters than they are plot driven. Only one of them, so far, has been a whodunit. Reading-wise, I’m all over the board. As long as the characters hold my interest, I’m good :)

Carol–I think your books market to your audience well. Your readers likely *know* what they’re getting based on your covers and your keywords and cover copy. So I think you’re being a savvy writer and drawing in those readers who *will* expect what you’re delivering.

I think the problem (and it’s really just a problem for *me*…poor Ms. Hannah to be an example in my post! It’s a good book…) is that “Woman With a Secret” is definitely a harder core, not lighter, mystery. It’s got a fairly disturbing crime scene (for my cozy blood anyway, ha) and elements of a police procedural and psychological thriller. And then we weren’t in the police officers’ brains when they had their revelation.

Perhaps it’s that those suspense-building techniques were overused or would’ve worked better with a little more information added to each succeeding one. Not enough to give it a way, but enough to give the reader a slight edge. I haven’t read the book, but maybe that could be what your fair-play mystery self is saying to you.

Carol–That’s sort of what I wondered too. I thought she might be new to the genre, but it looks like she’s written quite a few mysteries. More information, a building-on of clues, would have leveled the playing field for the reader, for sure.

Not quite a genre conflict issue, but when I read The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern, it was promoted as being similar to Harry Potter, which it is not. It is actually a sort of tragic literary romance novel, with magic. I loved the book, but I have friends who were disappointed by it not because it was a bad book, but because they picked the book up with certain expectations that were not met and felt as if they had been mislead or tricked into reading it.

On the other hand, I read Victoria Holt’s The India Fan, which is supposed to be a gothic romance novel, and it read more like a morality play with some undeveloped romance thrown in.

Melanie–I know just what you mean…it’s not that I didn’t enjoy the book, but I was a bit deflated when it didn’t meet my genre expectations. Sounds like your friends represent the dangers of messing with fulfillment of these expectations! I think we can expect a few disappointed reviews when we take this route.

Robert McKee’s Story and Shawn Coyne’s The Story Grid both emphasize what they call “obligatory scenes and conventions.”

Readers draw conclusions from your title, cover art, and copy. Betray those expectations at your peril. Major flaw in untrained writing, right up there with faulty story structure.

For those interested in more detail, Shawn writes extensively about OS&Cs at his blog: http://www.storygrid.com/genres-have-conventions-and-obligatory-scenes/ (and many subsequent posts.)

Joel–I love that phrase: obligatory scenes. Yes, that’s *exactly* what they are.

It’s sort of like putting an army on the front cover and then having a book with no fight scenes. Or having a misleading title that suggests one thing and delivers another. I think, if we decide to break the ‘rules’ of genre, we need to do so fully cognizant of the possible consequences.

Good points! I do have expectations when I read a genre book. One romance I read really annoyed me. I’d thoroughly enjoyed it until the very last page when the author suddenly yanked away the HEA and threw in a new curveball that really didn’t match the story. SO annoyed! I won’t be reading any more of her books because it bothered me so much. BUT, if I know it’s a book that mixes genres, I’m okay with it. :)

Blending genres is fine, we just have to choose which genre we’ll broadcast “set your expectations here” and then meet them.

A mystery with a romantic subplot doesn’t have to HEA because the expectations are mystery, not romance.

Jemi–It sounds like she also didn’t weave in that element and it jerked you out of the story. Which isn’t good on top of everything else!

Outlander seems to be an example of successful genre blending–romance, historical fiction, fantasy/time travel. But Gabaldon does stick strictly to most conventions in romance (attraction at first sight, building of physical and emotional relationship, betrayals and forgiveness, internal and external conflicts resolved in a happily ever after…); she just includes much, much more. Not all romance readers like her book, but all the most important elements of romance are there to satisfy a romance reader–no rule-breaking, only additions.

Rebecca–I think that’s an important point that you’ve brought up. It’s okay to *add* in many cases, but not *subtract* the genre elements.

My favorite genre to read (and watch) is psychological thrillers and I don’t want to know who the killer is until the end. Well I do, but you know, I don’t. I want to keep guessing. This made me think about it. Do I want to solve the case with the sleuth? Nope, I don’t think I do. Maybe I’m lazy or maybe I don’t want to know until the end, but give me herrings and clues and I’ll guess, but in the end I want to be surprised out of my chair.

Great post to make me contemplate on what I want to read in a mystery.

I would argue that resolution is not required (I’m a literary fiction fellow at heart) but that the revelation of insight into the protagonist’s view of a resolution or its absence is required.

I am a proponent of the novel as a means to see a series of events – a world – through the eyes of a character. The best books allows us to also feel a series of events as they unfold before the protagonist.

I think it is poor snooker to sell the story to the reader as a police procedural and not see the case to a close. It is entirely another thing if the odyssey of the plot is merely a backdrop for the emotional journey of the protagonist which we are invited to see.

The question for me is expectation.

Our example procedural which is merely a backdrop canvas should be declared as such to the reader early in the story. Perhaps in the first paragraphs.

Bob poured me another scotch. I’d spent eleven years working for him.

“It’s not a personal failure that you didn’t catch the sonbitch.”

I grunted. Old cops don’t sleep alone. They’ve a roomful of demons to keep them company. Most of them aren’t killers. Well. They’re not quick killers, anyway.

“When,” he started. “When did you think you were missing his game, though?”

Here in this example we set in the beginning the expectation for the reader that the rest of the novel will cover the events of “the one which got away.” We authors get to choose if we have a trite little twist at the end or if the story is the revelation of the thousand little cuts which run our protagonist from bright and engaged to stunned and reticent.

The story can be about one thing in form but entirely another in substance.

We don’t have to stick to form. We do have to stick to the mission of providing meaningful substance to the reader. Well, we have to if we expect not to be giving out vanity press publications away this winter as gifts.

Jack–Perfectly put and a nice example. It’s all about the set-up. I was genuinely looking for hints of what was to come in the story (maybe more than most readers) and it wasn’t very clear. When I was presented with a dead body, a couple of cops, clues and red herrings…yeah, I think it’s fair to think that it was going to be a whodunit. There were also signs that it was a psych thriller…hints of a dark backstory involving the (one) first-person POV narrator (rest of book was in 3rd). So, I was getting mixed messages. A clearer set-up would have been great.

I don’t have an answer to that, but it’s a fab question. I think that, when you break the rules, it has to have a formula of its own – adhere to some sort of interior cohesion. The Columbo mysteries come to mind: that paradigm broke the rules and changed what constituted “the game,” but it stayed consistent within itself.

Hope I’m making sense here….

Kathy–Right, that it’s a *purposeful* breaking of genre rules/conventions and that there’s a master plan. And, maybe as Jack and others have mentioned, some set-up or foundation for breaking these rules stated in some way to the reader early on so they can adjust their expectations. Good example with Columbo–they set up their own set of conventions and stayed true to them.